Blessed Vasyl put his life on the line to provide the Eucharist to underground Catholics.The cobblestone streets of Lviv in Western Ukraine are quaint, but if one has to walk through them on a rainy day, it’s a challenge to keep one’s feet dry. The ages have made the stones uneven, and puddles form in the most inconvenient places. But because the old part of Lviv is protected as a UNESCO World Heritage site, the cobblestone streets, which date from when this area was part of the Hapsburg Empire, cannot be modified.

Nevertheless, a walk around town, in any weather, is an architectural feast for the eyes. Amid all the old world charm in a city that is reminiscent of Vienna, it’s easy to walk right past the unassuming building housing the Apartment/Museum of Blessed Bishop and Martyr Vasyl Velychkovsky.

That would not have bothered Velychkovsky, who didn’t want to call attention to his residence in the years when he lived there, 1955-1969 — especially not from the Soviet secret police.

And a random visitor to the apartment in those years might not notice anything out of the ordinary. Entering the flat after climbing a flight of stairs, one would see a small room with a twin-sized bed, nightstand, armoire, and breakfast table. In a corner was a bookshelf and next to it a low dresser with some ordinary household items on top: a shallow dish, a goblet, a jewelry box. A few icons adorned the walls—probably not unusual, considering the deeply entrenched religious sense among the people, even if they were living under an atheistic regime.

But that dresser in the corner was actually the most important place in this apartment. In the privacy of this dwelling’s principal resident, or in the company of special visitors, it was transformed into an altar. The goblet became a chalice; the dish, a paten; the jewelry box, a tabernacle. A wall lamp, somewhat resembling a gaudy Christmas decoration, became the vigil lamp.

In hushed tones, Fr. Vasyl Velychkovsky conducted the Divine Liturgy, providing the Eucharist for himself and whatever Catholics were visiting him.

Beginning in 1946, the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church in the Soviet Union did not exist—officially, that is. It was made illegal, and although members of the Church who wanted to keep practicing religion openly could join the Russian Orthodox Church, many preferred to continue practicing in secret.

The bishops of the Greek Catholic Church had been arrested in 1945, and priests who were discovered to continue providing the sacraments could also be arrested.

Vasyl Velychkovsky, born in 1903 in Stanislaviv (present day Ivano-Frankivsk), became a Redemptorist priest in his 20s. After spending some time preaching missions in northwestern Ukraine, he became the head of a monastery in Ternopil. It was from there that he was arrested by the Soviets in 1945, accused of spreading anti-Soviet propaganda.

The Blessed Velychkovsky National Martyr’s Shrine in Winnipeg, Canada, describes his ordeal:

After one year of interrogations and tortures in the KGB prison in Kyiv, he was finally sentenced on June 26, 1946 to die by firing squad. He was on death row for three months. While in the cell with others on death row, he catechized them and prepared them through the sacraments for their coming death. When his name was called, he left the cell ready to die for Christ, but at that moment, his death sentence was commuted to ten years in Soviet labor camps.

He spent the 10 years working in a coal mine in Vorkuta, north of the Arctic Circle, where he continued to provide the sacraments as best as he could. Upon his release, he and Redemptorist Brother Irenaeus Manko took up residence in the apartment of an elderly Polish woman in Lviv and helped with her care.

One of the bishops who had been imprisoned in 1945, Nicholas Charnetsky, returned from a Siberian labor camp in 1956. Terminally ill, he spent his remaining years in prayer and guidance of the underground Church. As a result of his poor health, he died in 1959—in this Lviv apartment.

Charnetsky and Velychkovsky were among the bishops, priests, religious and lay people beatified by Pope John Paul II when he visited Ukraine in 2001. The feast day of the New Ukrainian Martyrs is June 27.

In 1959 Rome appointed Velychkovsky to be bishop of the underground Church in Ukraine, but there were no bishops in the Soviet-controlled territory who could ordain him. Except one. In 1963, Metropolitan Josyf Slipyj had himself just been released after 18 years in the gulag, part of a prisoner exchange arranged by Pope John XXIII and U.S. President John F. Kennedy. He was on his way to exile in Rome. Awaiting transfer in Moscow, he asked Velychkovsky to come visit him in the Moskva Hotel. There, he secretly ordained him a bishop and assigned him the responsibility for the catacomb Church.

The small apartment in Lviv thus became a cathedral. Velychkovsky presided over a secret seminary and ordained many priests here, in addition to continuing to provide the sacraments to those who visited.

“Here, early each morning he would quietly celebrate the Divine Liturgy in one corner of the room away from the window,” according to the Blessed Velychkovsky National Martyr’s Shrine. “In this room daily he would secretly meet priests and nuns and laity who would bring him requests for baptisms, marriages, liturgies, or for some holy objects such as crosses, holy cards, rosaries, etc.” From here, he instructed priests to go to cities and villages to conduct in secret Church services and sacraments wherever they were needed.

Anticipating being arrested again, Velychkovsky ordained new bishops. Among them was his successor, Archbishop Volodymyr Sterniuk, who eventually led the Church out of the underground in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Velychkovsky had a great devotion to Our Lady of Perpetual Help, and wrote a book, The History of the Miraculous Icon of Our Mother of Perpetual Help, which led to his second arrest and imprisonment.

“He was imprisoned in a psychiatric ward. They were using different psychotropic medicines on purpose,” said Taras Hul, caretaker of the Lviv museum, as he gave a tour in early May. “They beat him and used electrical cables as a punishment.”

But he continued to provide the sacraments, hearing confessions and celebrating the liturgy. A relative in Croatia would send him care packages that included raisins, which he would leave in water in order to make wine. Along with this he consecrated a few crumbs of bread. He would take his glasses apart, using one lens as a paten and the other as a chalice.

After three years, he was released and deported to Yugoslavia. He visited a sister in Zagreb, whose husband, a physician, tried to provide medical care for the frail bishop. But the “medicine” the prison authorities had injected into his system had already irreversibly damaged his nervous system and heart.

In Rome, he visited Cardinal Slipyj and had a private conversation with Pope Paul VI.

At the invitation of Metropolitan Maxim Hermaniuk of Winnipeg, Manitoba, Bishop Vasyl visited Canada, but stopped first in the United States.

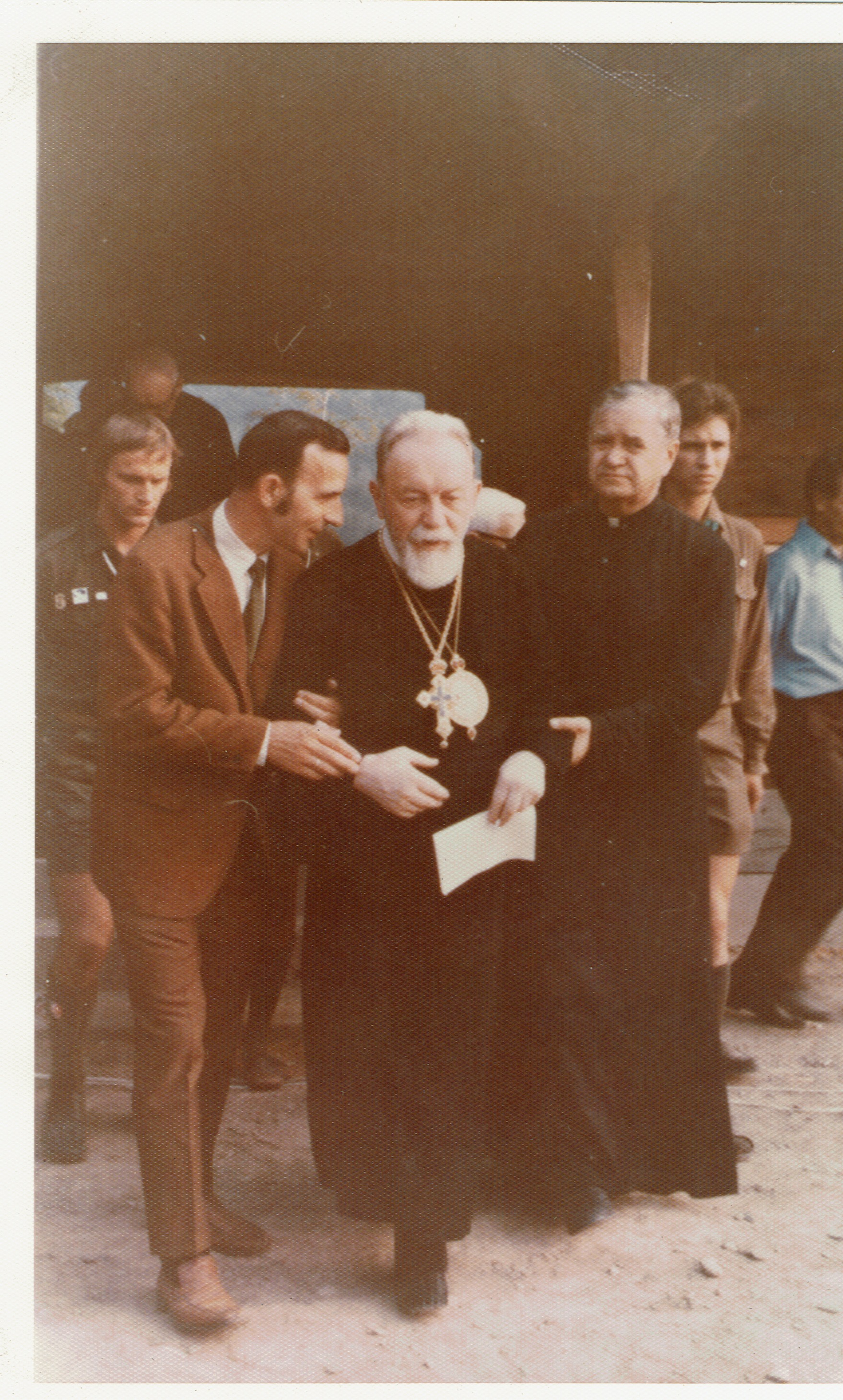

George Welyczkowsky, whose father was a cousin of Bishop Velychkovsky, was 15 at the time and attending a Ukrainian Scout convention in upstate New York. Unknown to the Welyczkowsky family, who had driven from Detroit to attend the convention, Bishop Velychkovsky was in New Jersey at the time. When the heard about the Scout gathering, he expressed an interest in attending and meeting the young people. George Welyczkowsky and his brothers thus had a brief encounter with him before being shepherded off to jamboree activities.

“I remember shaking his hand. His hands were like what I would imagine a boxer’s hands to be, you know, big, heavy, meaty hands, like he had labored a lot during his life,” Welyczkowsky said in an interview.

At a liturgy for the scout gathering, the bishop imparted his blessing and expressed his hope that “you may live to see the resurrection of our suffering nation.”

The date was August 24, 1972. Coincidentally, 19 years later, that date would become Ukrainian Independence Day after the breakup of the Soviet Union.

Bishop Velychkovsky proceeded on to Canada, and died in Winnipeg on June 30, 1973. After the beatification of the New Ukrainian Martyrs, on June 27, 2001, his remains were transferred to St. Joseph’s Ukrainian Catholic Church in Winnipeg, and were discovered to be incorrupt. His resting place has become a shrine. Its director, Redemptorist Fr. John Sianchuk, has been instrumental in restoring the Lviv apartment and tracking down many of the bishop’s personal effects and writings, as well as his KGB dossier and the testimony of people who knew him.

As George Welyczkowsky matured, he took more of an interest in Blessed Vasyl and has been to the apartment in Lviv several times, as well as the shrine in Winnipeg.

“There used to be a nun [in Lviv] who knew Blessed Vasyl well. She told me that he had a confidence that he carried with him,” Welyczkowsky said. “If the Soviets were coming and raiding places and arresting people, he never panicked. He never feared anything that would happen on earth. She remembers him confronting a lot of soldiers and stuff. He just carried himself with this incredible confidence and faith that it had an effect on people. The way she puts it, he had his eyes on the afterlife. … Just the way he conducted himself was different.”

The apartment does not have a website but does have a Facebook page, although it is in Ukrainian. The shrine in Canada arranges annual pilgrimages to Ukraine.