Father James Schall discusses the life and times of the “Wise Man from the West.”This year marks the 70th anniversary of the state-run Catholic Church in China, which appoints its own bishops and rejects the authority of the pope. These past seven decades have been marred by China’s expulsion of foreign missionaries, the jailing, torture and execution of faithful Christians, especially priests and bishops, and a tense relationship with the Vatican.

But the history of Christianity in China goes back much further than that, and the Middle Kingdom’s relationship with Western religions has been far more complicated. One of the pioneers of Christian evangelistic efforts in China was Father Matteo Ricci, a member of the Society of Jesus who arrived in the country in the late 16th century. The British historian Vincent Cronin wrote about Ricci’s life and his efforts to convert the Chinese emperor in a 1955 work titled Wise Man from the West: Matteo Ricci and His Mission to China. Ignatius Press has just brought out a new edition of the work, with a Foreword by Jesuit Father James V. Schall, Professor Emeritus of Georgetown University. Father Schall is the author of A Line Through the Human Heart: On Sinning & Being Forgiven (Angelico) and Catholicism and Intelligence (Emmaus Road Publications). He spoke with Aleteia about Matteo Ricci and his legacy in China.

Would you give a brief summary of who Matteo Ricci was?

Ricci was born in Macerata, east of Rome, in 1552 and died in China in 1610. He studied in Rome and joined the Society of Jesus. He was assigned to study in India and later in Japan and Macau, and eventually was able to enter China. He was the first European to enter the Forbidden City [in Beijing]. What made him particularly famous, besides his amazing memory, was his effort to convert the Chinese by first seeking to make himself culturally Chinese.

We take international travel for granted these days, but in his time it was an extraordinary journey to go halfway around the world. Why? What motivated him?

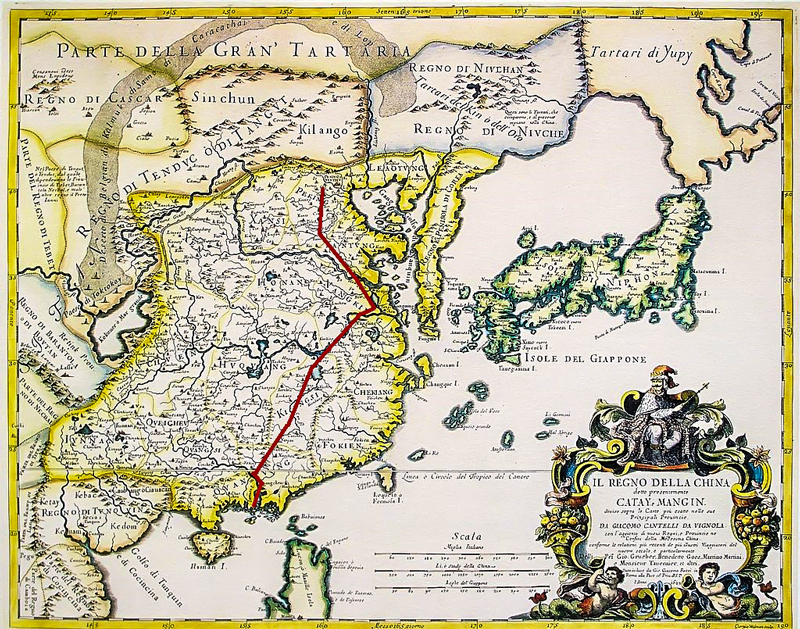

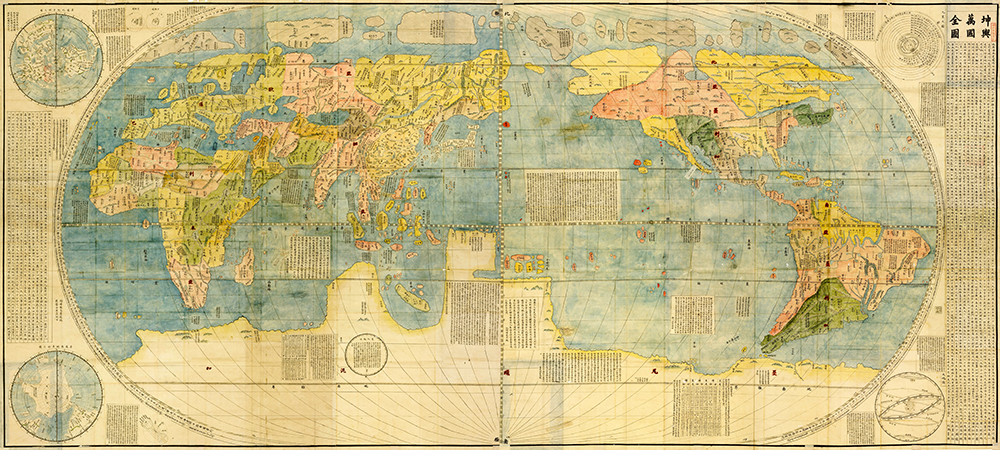

When Xavier or Ricci or John de Britto went to Japan, China, or India, they did not go by themselves. They travelled under the aegis of the Portuguese government and more or less under its protection. This whole movement east was designed as a way around Islam that controlled the land routes to Cathay in the orient. The Europeans were not quite sure what Cathay was. Part of the drama of Ricci’s life was to prove that the stories of Prester John and a fabled Christian kingdom in the orient was really what he came to know as China, the Forbidden Kingdom.

Thus, there were merchants, often pretty greedy ones, soldiers, government officials along with the missionaries who sought to pursue the gospel mandate of preaching to all nations. Often, the missionaries and the merchants opposed each other. My point is simply that in many ways it is not that much different today. If we can get from Europe or America to Delhi or Beijing in less than a day, the same conflicting motives exist. We might today compare Ricci’s efforts with getting to Mars, rather than getting to China. But even there, the motives would be similar. Not so much to convert the Martians as to keep an eye on the humans who set up shop on the Red Planet.

What were some of the principles guiding him in his evangelization of China?

Ricci was quite a learned man for his time in what we call today science. He knew something about construction, about languages, about geography, about astronomy, and about mathematics. The latter proved to be most valuable because the Chinese methods of calculating the sidereal movements according to which they ordered their calendar were faulty. While in Rome, Ricci had studied under the then famous Jesuit mathematician Christopher Clavius in the Roman College. Moreover, Ricci had received both as a boy and in Rome and in the Jesuits a thorough liberal education. He knew classical literature and philosophy. So Ricci went to China as a learned man, an accomplished man. This was important for the Chinese Mandarin class that Ricci encountered as key to the enterprise of converting China. China had to be shown that it was not, as it thought, the only civilized place in the world. In fact, there were people who had much superior knowledge in many ways than existed in China.

Ricci likewise understood that China was a proud people who considered themselves superior to every other nation and culture. It did not need, so it thought, anything but what it practiced in its own tradition. This meant, however, that Ricci had to learn how the Chinese thought and acted within their own sphere before he could broach the subject of another way of life that was not necessarily to deny the good things of Chinese culture.

What groundwork did he lay for future Christian evangelistic efforts in the Middle Kingdom?

We have to keep in mind that, in the long run, Ricci failed. This failure was not necessarily because he pursued the wrong methods but because the Holy See after his death decided that his methods were too close to accepting idolatry. The tentative Chinese path to evangelization thus never matured.

Much controversy has followed over the blame for this failure. In modern times, Ricci seems to have been vindicated if only by the failure of subsequent missionary efforts to do more than dent the still enclosed, in many ways, Middle Kingdom. The Chinese Rites, as Ricci’s efforts came to be called, have attained a kind of mystic status of what might have been. Ricci’s methods, by today’s standards of priority to the poor, would have been rejected by many as elitist. And it was, frankly, elitist. Ricci understood that the initial efforts he and his companions made to imitate poor Buddhist monks were not working and only served to brand them in Chinese eyes as losers.

Historically, Jesuit education has often been oriented to converting and educating the elite on the premise that they would, whether we liked it or not, be the future rulers and leaders. If Christians would not educate the elite, someone else would. In any case this was the approach that Ricci adopted. It looked for a while like it might work. He believed that if he could convert the Emperor, the rest of the nation might have followed. It was a gamble that just might have worked. It was cut short not by the Chinese but by the Europeans. What we see today is the Chinese rapidly acquiring the scientific and technological knowledge that they lacked, but not much budging on the issue of culture. The irony is, no doubt, that the official Marxist doctrine that the regime claims to follow is mostly a western product adapted to Chinese traditional ways.

Why isn’t China more Christian than it is today?

How Christian is it today is a highly speculative issue. The government is militantly opposed to anything that even slightly seems to undermine its authority. It is atheist in form. Nothing in public happens without its consent. When the Church appoints bishops, the government must approve every step of the way. Orthodox Christians often find themselves in jail for decades.

Some argue, with indirect evidence, that there may be five or six million underground Christians, who have to keep their rites and views within the family, not unlike the early Christians in Rome. The Vatican has frequently sought to establish diplomatic relations with China. But this would probably mean no relations with Taiwan and it is not certain that the Church would gain anything by it. We find it difficult to imagine the degree of control that the Chinese government holds over its citizens, in the family and in every other walk of life. The abortion and birth control policies are issues of public law.

It is not difficult to see why China is not more Christian. To be so in any meaningful sense would mean a dismantling of the whole bureaucracy. Efforts to get at converting the Chinese communist elites are every bit as daunting as efforts of Ricci to convert the Emperor. Indeed, they are no doubt more difficult. We forget that when the Soviet Union collapsed, the Chinese government did not. It changed its ways in one major respect. It decided to learn western science and technology but not its culture or religion. In so doing, China became richer and richer, the labor center of the world. While Ricci could show a connection between science and technology and Christianity in his time, in our time science is popularly thought to support no culture or religion.

This view may not be true, but from the Chinese view, they are only doing what they see is going on in the West. But the relation of science and Christianity is closer than many think. I recall Cardinal [George] Pell gave a lecture about China in which he recounted a study of Chinese economists. They tried to find the single reason why the West prospered while China kept getting mired in backwardness and moral corruption. After much study, they decided that the one reason was because of the religion in the West.

How is Ricci thought of in modern day China?

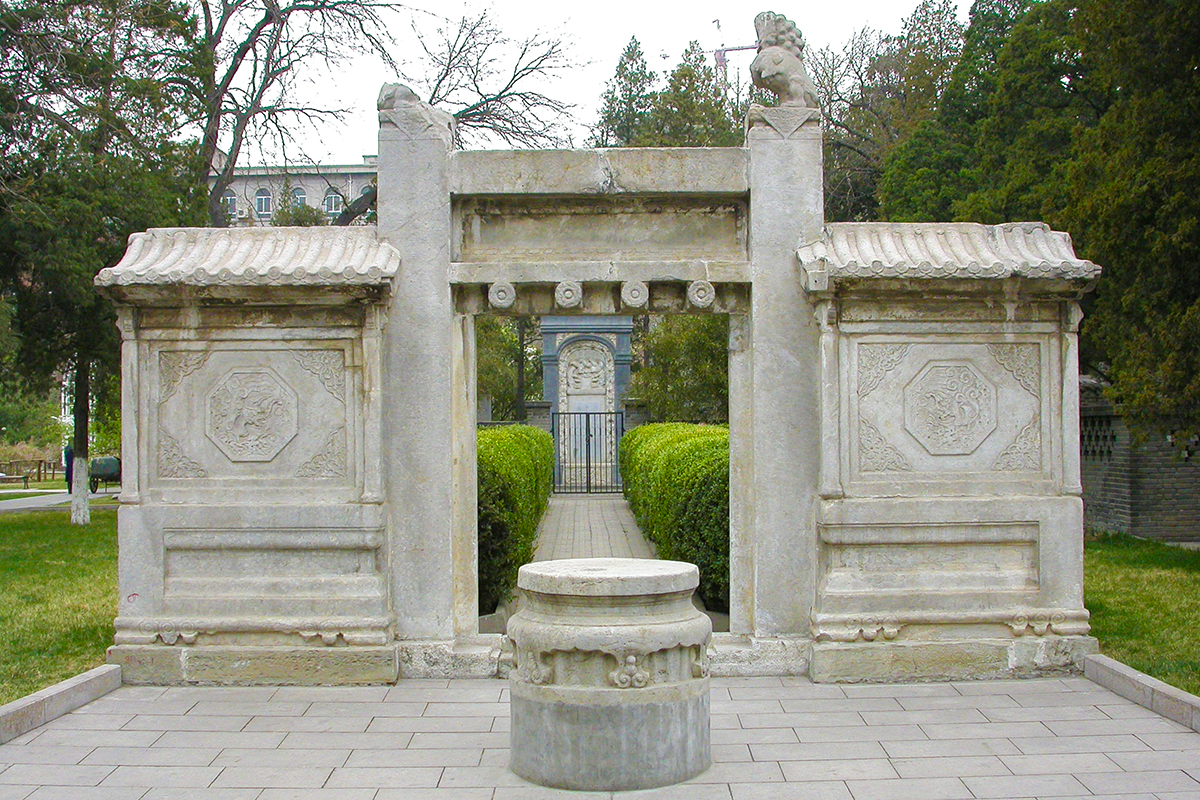

Ricci’s grave, along with those of other missionaries of his time, still exists within the confines of a Chinese university. It took many outside efforts to protect it and have it recognized. However, Ricci does seem to be recognized as a figure in Chinese imperial history. He is acknowledged for bringing some elements of more accurate science to China from the West in his time. The fact that Ricci and his successor Adam Schall von Bell are given much attention in the West is also a factor that keeps Chinese interest in these missionaries. They were in fact dealing with a momentous problem of how to go about changing a culture while keeping some of its ways.

China has always considered itself to be a superior culture. Other peoples around its borders—Korea, Japan, Vietnam—and others feel its influence. Its relation to Russia as well as to the Arab world is not so much of converting them to Chinese ways, but of controlling them for Chinese interests. Everyone who knows them finds something admirable in the Chinese people. China never broke up into smaller and more manageable units. In fact as hostility to Taiwan shows, the idea of more than one China is unacceptable. The result is a huge population and land mass that is probably unmanageable without the exercise of absolute power. Aristotle was opposed to such a gigantic world power as he thought it would take a divine mind to rule it. China has not proved he was wrong.

CHECK OUT THE GALLERY!